Dilemma: After perceiving eight decades of absolute loss in the world and bearing witness to the exploits of the poisoned species of man, how does one find hope? Nathaniel Tarn seems to solve this dilemma by nodding towards birds and trees as member species of his coveted clan, proclaiming them to possess extreme beauty, then letting his darker instincts peer out a bit from under the cuffs of his jacket. He wears his emotions on his sleeve. What punches does he need to pull now?

This is not to say that there isn’t an admirable quality to his unmitigated gloominess. Who am I to say he has not earned his world-weariness? I am not suggesting that his weltschmerz seems put on for size. Tarn has done more and seen more in his life than I presume I have in my last ten. And some readers may not find his darkness as remarkable as I do. They might see hope in his homage to those things that he finds beauty in as he resists the pressures of a ravaging world.

The ravaging world has become ever more present in this his 80th year. Tarn was born in 1928 in Paris, rose to become a leading anthropologist and a translator of Neruda. His influence on ethnopoetics is unquestionable. He is also unquestionably a great world traveler [the poems in Ins and Outs of the Forest Rivers find such settings as Sarawak, Borneo, East Malaysia, the Greek Islands, Megiddo (a hill in modern Israel), Los Angeles, Maui, Bali], and astute observer (particularly of birds).

The poems are almost never populated by specific humans. These are left out of the picture to a very large extent. Like a good anthropologist, he generally addresses humans in collective form. When the human world is invoked, it is almost always as a “we” (when Tarn wants to appeal to our sense of humanity) and a “you” when he wants to lecture humans on the errors of their ways. This seems very strange to me to have a book populated mostly by animals and ideas. But I believe that Tarn has had quite enough of endeavors so that their specific meanderings and tribulations are trivial. Indeed, compared to the geological time scale that Tarn’s work exists in, the human is unimportant.

Tarn takes this turn to such a great extent in the final (and title) piece of “Ins and Outs of the Forest Rivers” that we learn only in the endnote that during the trip that inspired the poem his friend and colleague during the trip died halfway on the trip out and how Tarn had to arrange for his removal from the forest. All this at the age of 80. Yet nowhere in the poem is there any mention made of the colleague’s calamity. Instead, Tarn is true to form, remarking on several bird species and talking of imminent encroachment on bird habitat. The birds are his angels: Kingfisher

Buceros [Rhinoceros Hornbill]

Terpsiphone a! paradisi [Asian Paradise Flycatcher]

These are the stars of his poems in which nature can do no wrong. I would not completely refrain from using the term “romanticized” notion of nature, for its harshness and vicissitudes are never mentioned. The term “food chain” does not appear once! Even the animals he refers to are very well-behaved. Tarn’s role, then, is as the birder/witness come to drink in the scenery and gather what he can about the differences between human social behavior and how birds behave in their tree canopy.

It is also interesting how Tarn refers to these birds by their scientific name instead of their common name. In this way, he also makes reference to Celan in what I believe to be Celan’s native Romanian in one epigraph for “La Citta´Morta.” Tarn is ever the one for scholarly exactitude, and perhaps one could say of him like Eupolis, an Athenian comic playwright, said of one of his influences, Pindar, that the poems of Pindar “are already reduced to silence by the disinclination of the multitude for elegant learning.” Could it be that in modern times, too, Tarn, like Pindar, is more respected than read?

Let us not give in to our age’s ignorance completely (though I think Tarn has, in fact, already acknowledged this kind of capitulation). There is reason to read Tarn if we need to be reminded of how man, in the name of “progress,” so often overreaches, how the irritations of modern life juxtaposed against the majesty of the untrammeled natural world.

These moments of juxtaposition are an indicator of what Forrest Gander refers in a recent Harriet Blog post (see below), as environmental literacy.

The United States and China are locked in a tug of war to determine which country can spew more carbon. For both, natural resources are plundered for short-sighted ends. Perhaps these facts place particular responsibilities on the poets of both countries. Maybe the development of environmental literacy, by which I mean a capacity for reading connections between the environment and its inhabitants, can be promoted by poetic literacy; maybe poetic literacy will be deepened through environmental literacy.

Tarn’s switches between the excesses of the modern world, its blindsightedness, and the natural set up the “connections between the environment and its inhabitants.” The associational qualities of poetry make it an excellent vehicle to pursue these relations. I think probably pursues them better than fiction, which must always be plot-bound to a much greater extent.

These moments of juxtaposition are also, for this reader, the most satisfying parts of the book. One moment in “Hummingbird-Sandwich” he will be rhapsodizing about the virtues of gardening and the next he will be damning the irritating calls of solicitors looking for donations to feed the vast numbers of hungry and homeless elsewhere in the world. Then he calls down the hummingbirds to be witness to his good deeds the way gods would come down to witness the past good deeds of humans. Lamenting the passing of the gods, he desires for Nature to come and bear witness to his acts of kindness. He says, “Let hummers come in then or perish in a sandwich.”

This is one of the very few moments of levity in the book which usually inhabits a much more serious tone. Usually, very serious, condemning, perhaps even with a vengeance for modern life. But this moment of acknowledging the absurdity of man’s interaction with nature provides a different window, if ajar only for a moment. Its presence raises a question for as a reader. The experience of reading a text that demands justice and equality for nature is well-documented [Tarn’s texts are but a few in a long litany]. However, is there much of a tradition for comical interaction with birds and species outside of the human in general? I guess it can’t be expected that animals have a sense of humor, or perhaps humor is so species-specific that one couldn’t expect a hyena to laugh or a hen to cackle. One means of approaching, it seems, the comical side of nature is in the anthropomorphizing of animals. I could expect Tarn to scoff at human hubris in projecting our mental life onto animals (at least this is why I presume he never engages in any anthropomorphizing of his animal subjects), but this act of awkward empathy is often the most sympathetic effort we can make as humans. Without placing ourselves into the mental, and therefore emotional life, of animals we are never going to get past the point where Tarn would like humans to be: beyond our anthropocentrism. In fact, I don’t trust anybody who doesn’t anthropomorphize animals once in a while . . . or even routinely.

Too much of Tarn, for this reader, is as witness, watcher, locator, namer of the natural. His birding tendencies get the best of him. I respect birders in their quests to see. Some, in my opinion, go too far in trying to catalog these events with a “life list.” However, I question whether the extent of one’s interaction with nature must be the visual (or in the case of birdsong — auditory). Where does play enter into the picture? Would this signal encroachment for Tarn? I would like to ask him this.

Certainly there is very little that is gestural in Tarn’s engagement of the natural world. the gardening is the one indication of the speaker moving his hands. However, there is a premium placed on human gesture as redemptive. In “A Smile” after, once again, Tarn has contemplated the absence of humans in this world at some distant point in the future, Tarn anthropomorphizes Juniper as mother and Piñon as father, Juniper waving with her many yellow hands. Then, quickly, he shifts to the abominations of the modern by invoking “seven cool million tons of bombs” and “tortured prisoners” which lead to

defoliation, that especially, the dying trees around

. . . a devastated head, beauty devoured by age, needles

of grief worn deep into the skin, small rivulets

of patience also, running down cheeks

into the chin and neck: the mirror image of the face

that’s watching it across the room, a face

broken on the same wheel, a marriage wheel

of fortune—though all’s been positive to date!

Even the grief! Time passes and will not

be seized in any way, will not allow itself

to be held down by its frail shoulders,

arrested, stopped there in its tracks to be enjoyed.

It must, alike all else, be seized against the wind,

caught on the wind—“eternity” some said. Yet, still

from time to time, the smile may flash, the smile

still dazzles and whole lives light up—as if

illuminated by a tender fire, a burning, not

destructive of our wood, but granting life, quick,

urgent life, inclusive patience and refreshing love.

The sentiment at the end is rooted in the mother’s smile, the Juniper mother. It is an extraordinary sentiment, one that requires a great act of imagination to tease it out from the Juniper. However, I wonder if a smile’s capacity for “whole lives lighting up” appears a bit too Debby Boone. Perhaps I am just allergic to earnestness, that heartfelt moment that should cause a clamor in the soul but to me feels too much like schmaltz, a moment of overt sentiment strictly to produce an effect.

The book is organized into four parts. The first section deals with poems that contemplate death, the animal world, gardening (some of the best of this section) and an examination of Matthias Grünewald’s altarpiece circa 1526 in Alsace, France. The second section is entitled “Dying Trees” and it deals with the devastation of trees in the American West (the subject of “A Smile”). The third part is entitled “War Stills” and the main themes are of mindless devastation of the environment and the mindless pursuit and guarding of property that is at the heart of so much of modern warfare, particularly the madness that is the Iraq War. The fourth section, (in the reader’s opinion, the most effective) is the one which aims most effectively at distinguishing the relationships between the natural world and man’s civilized and urban instincts. The final section “Arawak” is comprised of the long title piece mentioned above that documents the loss of the natural world and its impact on the indigenous tribes.

Ascending Flight, Los Angeles

It is characterized by a pale subtle happiness of light and sunshine, a feeling of bird-like freedom, bird-like altitude, bird-like exuberance, and a third thing in which curiosity is united with a tender disdain. —Friedrich Nietzsche

1.

Seen face to face in a domestic converse:

no compassion. Seen in a group of persons

in social converse, none either. Seen solo

waiting, far off and isolate, colorless as

a grounded, wingless, songless passerine,

compassion’s ocean rises, flooding chest

chasm, a fraction further, extrudes tears up

and into eyes. Here, vastness of the Angels’

heart downtown, close to all arts and music,

sparsely filled up with buildings, their al-

zebras in crazy inundation of Californian

light. Always a few degrees above our own

and riotous with varied flowers and greens.

Airwise, blinding green parrots and such e-

xotica as might seem to belong here crackle.

Little Tokyo, Little Beijing, good rebates on

blouse-grown wings. The tears sink down to

rest in curiosity. Inveterate explorers wake.

Abandoned leftwing veterans rot on streets.

Beyond a world mayhem continues. Crying

sees murder; curiosity: consumption. through-

in a day, hang out, eat, drink, shop & consume.

2.

Birds from colorless to color: flowers color

to colorless. To stop life’s turn to nightmare

adopt the colorful patience of birds. Flowers

take flight and become birds, add color to

the birds in sky, so high, their colors hit in-

visible. This is the level we desire to reach:

bird high, plant low—famose cosmogony.

Out there in Hollywood, air-breasted women

trying to become birds and failing even, why

at ascent to flowers! To conjugate, lone mind,

all that is beautiful way and above all man, &

human understanding. Planes in their traces

along sky move white from unknown city-

unknown city, and this for no known purpose

you can witness low—but bird is clear in

purpose how much high, as hummer was at

nose the other day while gardening. Since I

was raising flowers to the power of air. As

child, remember Mitchell in the movie, eyes

up intently at a lone seagull—and she’ll be

loveliest ever to fly, him whispering, and so

she was in metal clad, flying countries alive.

3.

In cities, when the noise by day is overwhelming,

birds have evolved in time to sing by night, thus

to be heard by other birds. That’s what we birds

are doing now, that once were poets of the day.

We sing at night, all hope on standby, but we are

heard by our own kindred. Meantime, deliberate,

people may rot into sweet angeleños. We crummy-

nals! dropping them there while shopping! O! O!

Wait! Wait! For ages now I shall read self-same,

very same book over and over, not skipping book-

book, place-place, or landscape-into-landscape.

I’ll persevere presentially with one enlightened

me, ago when we could not even climb castles.

My darkness lifted and, suddenly made mirror, I

sent back simple verbs to one scale of our time.

Emotions are dead leaves; yet some may carry

to sing as if a world were morning, as if light,

still tinted by the birds, were truth and possibly.

After the night, after angelesque dreams, a great

light sphere rolling into the room, a rubber cage

with convict bird inside—clothed in all colors

the despised can dream. World granted. Novel day.

The most gratifying thing about this poem for poets should be that we, as poets, are the chosen people according to the birds, that we poets are ones who have evolved to sing by night. The idea of birds evolving to sing by night is the kind of observation about animal and life and the natural world that I expected more of during the course of the book. As an apparently lifelong veteran birder, I had hoped to learn about more specificaspects of unusual bird behavior, something that would make me stand up and say, Wow, would ya’ look at that? But these moments were too few. This poem also offers up my favorite line of the book: “To stop life’s turn to nightmare adopt the colorful patience of birds” This just about sums up all of the didactic turns that Tarn is taking in the book.

Technically speaking, there are some interesting things going on with this poem as well. The unusual hyphenation at the ends of some lines lends to multiple suggestions. I especially like the “e-xotica.” This is very novel manipulation and underscores the juxtaposition of our current e-crazed phase of development with the birds. “Crummy-nals”? This bordered on being a little too cute for me and again a bit heavy-handed. Most of the piece seems like an accumulation of fragment; therefore, the piece feels very dense as one reads it, and its turns are quite labyrinthine. Those readers who do not bring a ball of string with them, may be eaten by the Minotaur.

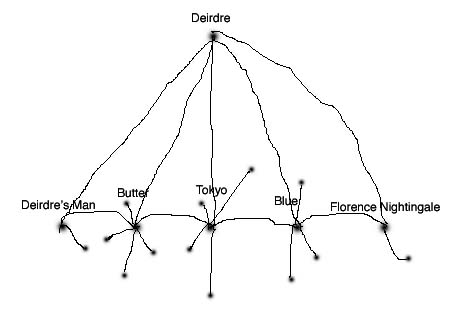

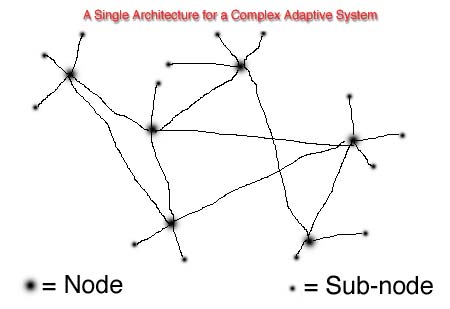

All five sections of the book are preface by the prefatory poem Pursuit of the Whole & Parts. In this poem Tarn provides philosophical meditation of the relationship of the individual to the larger world-system outside of the individual. Tarn says that the perception of the general is not sufficient without the particulars to coincide with it. He goes further that it is the moment of those particulars crystallizing in a moment of gestalt where one can rationally pursue the general, the whole, the “firefly of spirit” again. Once that crystallization occurs it may recur in various forms, endlessly like the patterns of nature themselves. This sounds very much like the idea of “attractors” in non-linear dynamical systems. I wonder if this is what he may have had in mind as he tried to poeticize this concept. As a piece of poetry-philosophy, it is one of the finest in the book.

However, I would take issue with the line “the selfishness of the light-hearted, the cloud-walker, alone with his invisibles, his intangibles, all those angelic wings . . .” It seems to me that he might be thinking about a different concept of light-heartedness” than I am used to or he is attempting to excuse his own darkness as that which is necessary for the kind “firefly of the spirit” to arise. Perhaps because my own temperament seems to be so far from such heft which Tarn considers to be the opposite of selfishness, I object to this characterization or at least confess that I do not understand what Tarn means. But if rightly interpret Tarn as meaning that the considerate man is by all manners dark and brooding over his many unnamed and unrecognizable atrocities (which presumably would indict all contemporary urban humans), then I might detract from this position by pointing out a little light-heartedness sometimes can be a better teacher than the perpetual extolling about the woes of the world. Can one reach a point where one has witnessed too much?

Tarn’s project in Ins and Outs of Forest Rivers is that of the impassioned environmentalist who, seeing the horrible disfigurement of the natural world, will not go quietly into that good night. He has set upon a group of particulars that has locked into place as a conceptual whole. He gets the picture, and he is going to carry out his versification to that aim. Perhaps his age sets him toward the goal of preservationism. One tends to want to preserve everything. The hint of progress means the world is getting up and taking a few more steps without you. I remember this in my mother quite well, who, a few years before she died, took to standing out in front of a bulldozer and a contractor’s team which wanted to cut down a huge oak tree just off my parents’ property line in order to build a new road. She stood there in a showdown with them for three days until they got a court order for her to desist. When she told me about it, I was shocked that she had found such a passion for a tree. Assuredly, it was a beautiful tree, but I had hardly known my mother to put up a fight before this moment. In fact, she had idly stood by while my father had felled scores of trees in the past.

Hopefully, some day I will inherit some of her sentimentality.

I wanted to directly and vigorously connect in a prolonged manner with this book in the worst way, but I found in the fits and starts that I devoted to it, that I could not sustain any long sittings while reading it. I chipped away at the book and then came back to re-engage with some of the pieces. I think this is perhaps the way Tarn intended for it to be read. If it is not, I can only provide the usual excuses of not having sufficiently large blocs of time to dedicate to it or perhaps I am part of the “multitude not ready for elegant learning.” Or the attention span needs some Cialis. Whatever the case, Ins and Outs of the Forest Rivers is a book for anyone who tends to perk up when the conversation turns toward the abuses and devastation of man. Though it does not always seek to display the full variety of colors desired in elaborate plumage, it quietly instructs to adopt the colorful patience of birds, both overtly and as an object lesson.